The story of Psyche, like many Greek myths, is one of great drama and passion. Psyche, a mortal princess, is cursed by Venus who is jealous of her beauty, which has inspired many to worship her rather than pay their respects to Venus. She sends her son Cupid to shoot an arrow at her to make her fall in love with a monstrous creature. Instead, Cupid scratches himself and falls in love with Psyche. Abandoned by her family, she is saved by Zephyrus, god of the west wind, and carried away to Cupid’s palace where she is waited on by invisible servants. There, Cupid visits her every night but she is not allowed to see his face. Encouraged by her jealous sisters, she lights a lamp one night to see her lover’s face and injures Cupid in the process by dropping hot oil on him and he flees. She travels the earth searching for him and entreats Venus to help her. Venus instead sends her on a series of impossible tasks, the fourth of which is to take a golden box to the underworld to obtain a dose of beauty from Proserpine. She is told not to look in the box. Like Pandora, however, she cannot resist and opens the box, finding within it not beauty, but sleep, and she falls into a deep slumber. Cupid eventually finds her, takes her to Zeus, who allows her to become a goddess and marry Cupid on equal terms.

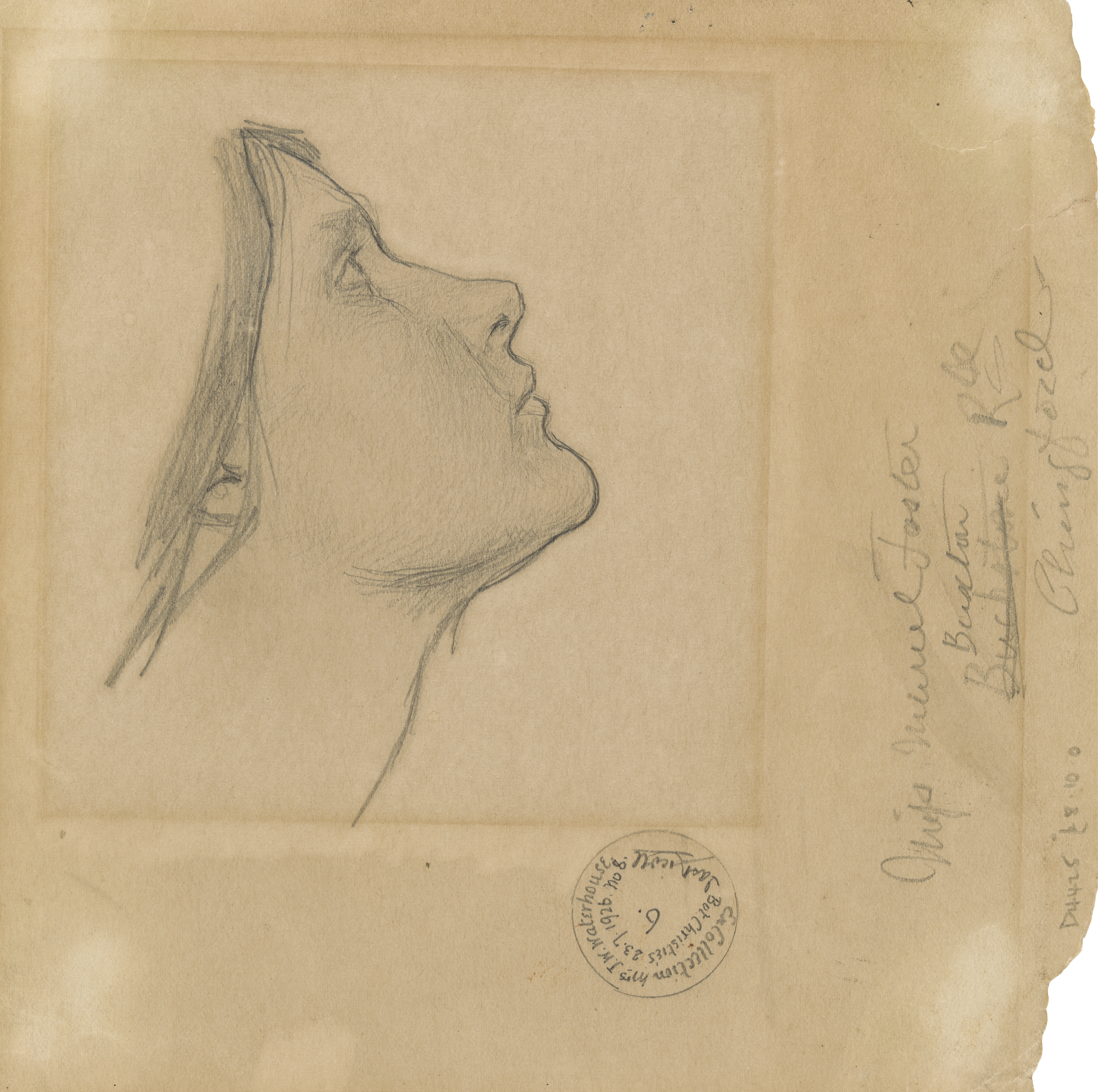

Waterhouse painted many mythological subjects including several depictions of Psyche: Psyche Entering Cupid’s Garden, 1904 (Harris Museum and Art Gallery) and Psyche opening the Golden Box, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1903 (private collection). The finished picture shows Psyche, seated in a dark wood, bending her head low as she peers into the slightly open box. A small plume of smoke rises from the interior. Fewer than 150 preparatory sketches by Waterhouse are known. They consist mainly of model’s heads – generally the most important element of the painting – in chalks. Here we have a typical preparatory sketch, confidently exploring the composition with fluid strokes, exquisitely modelling the flesh of the shoulder and back of the model. Not much is known about Waterhouse’s models and while it has been argued that he had a single muse who he returned to repeatedly over the decades (Miss Muriel Foster has been identified as a contender), it may also be the case that he chose a series of women with the same swan-like neck, doe eyes, modest features, full of understated grace that made his paintings both sensual yet innocent; a duality that has delighted viewers for more than a century.