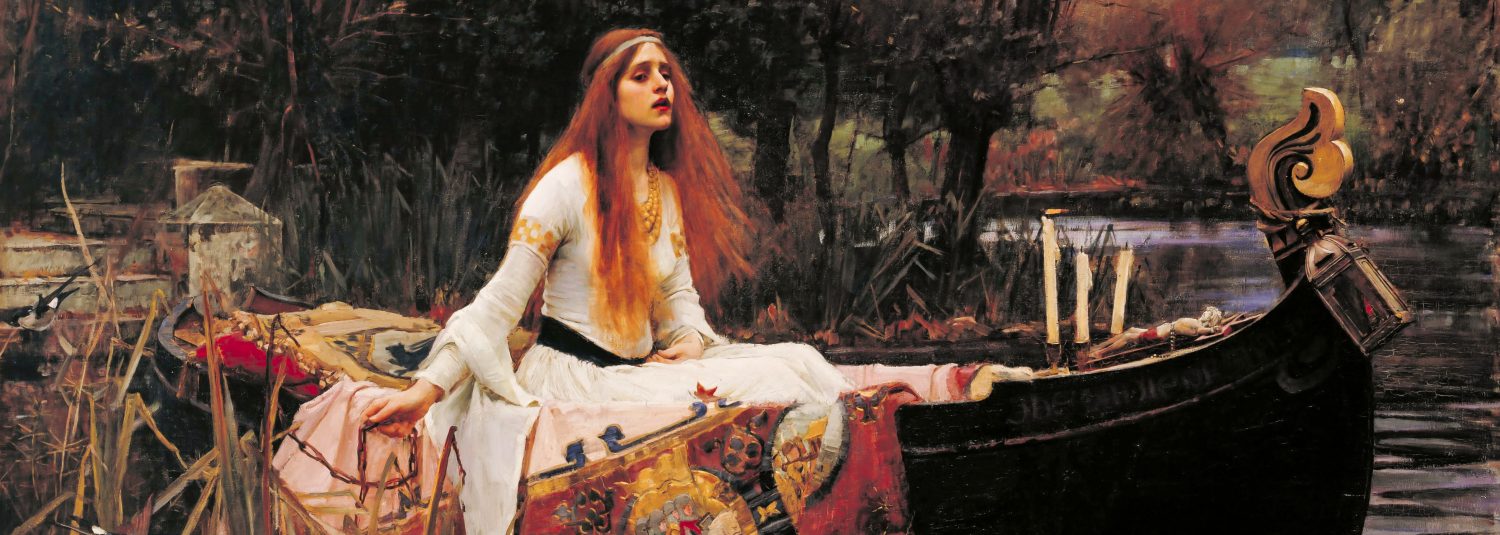

Reclining and facing the light, a lone woman plucks feathers from a fan and watches them float in the air. She seems completely removed from everyday life, yet in this languid state there is a sense of beauty emphasised by the sunflowers, the decorative rug, cushions and curtain, and the warm tone of the painting. The Italian phrase dolce far niente means ‘the sweetness of doing nothing’—the pleasure of being idle and blissfully lazy. Painters of the Aesthetic movement, as Peter Trippi points out, favoured the theme of idleness because it ‘liberated them from illustrating narratives and pointing to morals, seeking only beauty through harmonious arrangements of form, line and colour’. (1) William Holman Hunt had exhibited his own Il dolce far niente in 1867 and, although he griped about the creation of works that existed only for the ‘mere gratification of the eye’, he enjoyed ‘the opportunity of exercising [himself] in work which had not any didactic purpose’. (2)

A contemporary of the Pre-Raphaelites, John William Waterhouse is known for embracing the Brotherhood’s subject matter and style, and he shared their interest in Italy as a key source of inspiration. In 1871, a critic for The Art Journaldescribed a new style of painting by artists who ‘cherish in common, reverence for the antique, affection for modern Italy; they affect southern climes, costumes, sunshine, also a certain dolce far niente style, with a general Sybarite state of mind which rests in Art and aestheticism as the be-all and end-all of existence’. (3) Although Waterhouse was not one of the artists the critic was discussing, it was in this spirit that he painted two distinct works bearing the same title. (4)

Dolce far niente 1879 presents a stylistic change for Waterhouse. Inspired by Dutch painter Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s shift to lighter tones in the 1870s, he began to ‘open the shutters of his gloomy classical rooms’. (5) Despite the muted, antiquarian setting in this work—hinted at by the white mottled wall and the oil lamp that hangs before it—the painting appears fresh and modern.(6) Waterhouse experiments with the effects of sunlight on his figure; his use of short brushstrokes adds texture to the painting and is particularly effective in capturing the contrast between the three floating feathers and the white wall. (7)

Honouring the Pre-Raphaelite’s dedication to ‘truth to nature’ and of layering symbolic meanings in their paintings, the sunflowers that appear at the lower right of the composition and in the background are a critical component of Dolce far niente. Sunflowers represent adoration and self-admiration, a meaning made familiar in the mid-to-late nineteenth century through the popular literature of the language of flowers, (8) and the theme echoes through the scene—the woman feels at ease with herself, content doing nothing, basking in the sunlight like a sunflower blooming in the summer. Emblematic of the Aesthetic and Arts and Crafts movements, sunflowers became a fashionable and much-used design element, so much so that it was acidly commented upon in a women’s journal: ‘a blue pot and a fat sunflower … are all that is needed to be fashionably aesthetic.’ (9)

– Bianca Winataputri

1. Peter Trippi, JW Waterhouse, Phaidon Press, London and New York, 2002, p 43.

2. Judith Bronkhurst, William Holman Hunt: A catalogue raisonné, published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2006, vol 1, pp 187–8.

3. The Royal Academy, The Art Journal, 1 July 1871, p 176.

4. Dolce far niente 1880 is in Kirkaldy Galleries, Scotland.

5. Trippi, p 43.

6. Elizabeth Prettejohn, Peter Trippi, Robert Upstone and Patty Wagemen, JW Waterhouse: The modern Pre-Raphaelite, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2008, p 80.

7. As above.

8. Trippi, p 43; the language of flowers attributed meanings and symbolic associations to plants, flowers and floral arrangements that had been practiced in traditional cultures throughout Europe, Asia and the Middle East. The dictionary of floriography, Le langage des Fleurs, by Louise Cortambert (writing under the pen name ‘Madame Charlotte de la Tour’) was first published in 1819.

9. Quoted in Debra N Mancoff, Flora symbolica: Flowers in Pre-Raphaelite art, Prestel, Munich, Berlin, London, New York, 2003, p 72—the significance of sunflowers is also discussed pp 9, passim 64–75; correspondence with Carol Jacobi.

One thought on “Dolce far niente”

Comments are closed.